“What you kids up to?” His voice was shrill and strident. From the look of it I would say, just offhand, that he had changed it last somewhere around the time Lyndon Johnson died. When he got closer I saw it was a back brace. No shirt instead there was something cinched around his waist that looked like a lady’s corset.

He was wearing green old man’s pants and lowtopped Keds. He had a good case of psoriasis going on the bald part of his skull. His hair was long and scraggy, what little there was left of it.

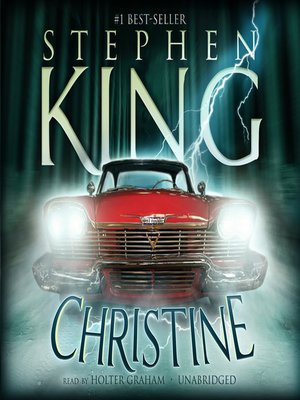

This particular dude struck me as the sort of man who enjoyed very little. It was an old guy who looked as if he was enjoying-more or less-his seventieth summer. “Looks like the Russian army marched over it on their way to Berlin,” I said. I reached in and pulled up a little puff of upholstery, looked at it, and blew it away. Once, twenty years before, it had been red. He got in and sat down on the ripped and faded back seat. Arnie didn’t seem to notice that, either. A hot, stuffy billow of air, redolent of age, oil, and advanced decomposition, puffed out of the open door. Instead, there was a kind of goofy madness I didn’t like much. He knew how to joke, but there was no joke on his face then. I’ll take you home and put you under the frigging air conditioner and we’ll forget all about this, okay?” But I said it without much hope. “It’s sunstroke, right? Tell me it’s sunstroke. “Arnie, you’re having me on, aren’t you?” I said. He tried the back door on the passenger side, and it came open with a scream. He was running around the car like a man possessed. “Look at her lines, Dennis!” Arnie whispered. There was an old and sun-faded FOR SALE sign propped on the right side of the windshield-the side that was not cracked. Worst of all, there was a dark puddle of oil under the engine block.Īrnie had fallen in love with a 1958 Plymouth Fury, one of the long ones with the big fins. The others were bald enough to show the canvas cording. It looked as if someone had worked on the upholstery with a knife. The back bumper was askew, the trunk-lid was ajar, and upholstery was bleeding out through several long tears in the seat covers, both front and back. The right rear deck was bashed in, and an ugly nest of rust had grown in the paint-scraped valley. The left side of her windshield was a snarled spiderweb of cracks. She was a bad joke, and what Arnie saw in her that day I’ll never know. I went back, thinking that it was maybe one of Arnie’s subtle little jokes. His eyes were bulging from behind his steel-rimmed glasses, he had plastered one hand over his face so that his palm was partially cupping his mouth, and his neck could have been on ball-bearings the way he was craning back over his shoulder. “Oh my God!” my friend Arnie Cunningham cried out suddenly.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)